The appointment of a liquidator has long been criticised by Attorneys at law, many of whom have found the process opaque and discriminatory in relation to the number of estates allocated. Gender considerations have also been discussed. Creditors, bankrupt parties, and Attorneys at law have also criticised the high threshold applied by the courts in matters regarding the reprimands of liquidators and their dismissal.

In the spring, Bjarki Már Magnússon, lawyer, wrote a master´s thesis at the Faculty of Law at Reykjavík University entitled "Liquidators in bankruptcy estates – the appointment of liquidators, reprimands and dismissals" and, during his studies and after graduation, he has assisted Attorneys at law at LOGOS legal services in carrying out the liquidation of bankruptcy estates.

Bjarki Már was granted access to data from District Courts, which he then processed and analysed in his research. The Bar Association‘s Journal asked Bjarki Már about the thesis.

What was the research about and what are the main findings?

The research focused on the appointment of liquidators on the one hand and on reprimand cases on the other. The results were varied. For instance, the District Courts could better ensure that prospective liquidators are free from conflict of interest before an appointment is made. It would be desirable to improve the procedures for managing information on liquidators, which serve as the basis for their selection in accordance with the Non-binding Rules on the Appointment of Liquidators and the Supervisor of Composition Proceedings no. 2/2019. I believe the aforementioned rules have been of significant benefit, but several issues need further examination. For example, the considerations that should underpin the appointment could be arranged in an order of emphasis, and it would be beneficial to establish rules regarding the liquidator´s facilities for larger estates. Consideration may also be given to whether the District Courts should be granted the authority to temporarily remove a liquidator from the liquidator list in cases of breach of duty.

In addition, it was notable how strongly District Courts outside the capital area favoured appointing Attorneys at law with offices within their district. In my opinion, that should not be a decisive factor in the appointment of liquidators.

Has research been conducted previously on issues related to reprimand cases regarding the work of liquidators?

To the best of my knowledge, my research is the first ever conducted, which was quite surprising considering the number of cases that have come before the courts and the interests that may be involved. It should be noted that there are currently conflicting conclusions in court cases on standing in reprimand cases, creating some legal uncertainty. I am referring to the fact that the Court of Appeals found in cases no. Under 81/2019 and 647/2020, the creditors’ claim must be approved for him to have standing in a reprimand case. The District Court of Reykjavik, on the other hand, has reached a contrary conclusion, despite the aforementioned recent precedents of the Court of Appeals. After my examination of the case, I believe there are arguments that the District Court's conclusions are correct and that they are supported by legal explanatory documents. Additionally, the procedural rules for reprimand cases are, in my opinion, vague, and I believe that they need to be revised.

Do you consider the requirements imposed on liquidators to be too low?

The outcomes of reprimand cases suggest that the bar set for liquidators is too low: it takes very significant circumstances for a liquidator to receive a reprimand, and, based on the case law, it is almost impossible to remove a liquidator from his position. Regarding the appointment of liquidators, one can argue that, for larger bankruptcy estates, they should be assigned to experienced Attorneys at law with substantial expertise. Accordingly, stricter eligibility requirements could be set for Attorneys at law in such estates.

What changes do you think are needed to remedy this?

To address the shortcomings discussed in the thesis, both legislative amendments and changes in court practice would be required.

First, it is worth considering whether the legislator should decide that the allocation of bankruptcy estates be confined to Attorneys at law. Under the current Bankruptcy Act, it is not a requirement that an appointee be an Attorney at law; completion of a master’s degree in law suffices. In practice, however, only Attorneys at law are appointed as liquidators, and the guidance on appointing liquidators likewise refers to Attorneys at law rather than lawyers generally. Secondly, I consider that the procedural rules applicable to reprimand cases under Article 76 of the Bankruptcy Act should be reviewed; I set out the reasons for this in the thesis. Thirdly, one might consider legislative amendments to eliminate legal uncertainty regarding standing in reprimand cases. I also consider it necessary to examine whether decisions and rulings of the District Court in reprimand cases ought to be published. In my view, publication would be beneficial, as it would allow for lessons to be drawn from prior decisions. Finally, I consider that Article 76 of the Bankruptcy Act should be supplemented with a provision that, if a liquidator resigns or is removed, they must deliver to the District Court all documents in their possession relating to the liquidation. No such provision exists in the current legislation, whereas a comparable rule can be found in the Danish Bankruptcy Act.

Legislative amendments are not necessary in all cases. For example, the courts could modify their practice by contacting an Attorney at law before appointing them as a liquidator, enabling the Attorney at law to confirm whether any impediments to the appointment exist. In addition, the Judicial Administration could amend the non-binding rules governing the appointment of liquidators if it considers that further rules are needed.

Creditors' interests should carry greater weight

How do you consider creditors' interests are best safeguarded in relation to the liquidation?

That depends on the scope of the liquidation. In larger estates, in my view, it is necessary to appoint an experienced Attorney at law to conduct the liquidation, and, in assessing whether an Attorney at law is the right person to liquidate a particular estate, it would be appropriate to consider their expertise. Such an appointment is not always necessary, for example, in estates with few or no assets where no extensive recovery actions are anticipated. District Court judges and judicial assistants should, in larger estates, place greater emphasis on a liquidator’s experience and expertise, and, in my view, the liquidator’s place of residence and considerations of equal distribution of appointments among Attorneys at law should carry less weight. In other words, in larger estates, the creditors’ interest in securing the most competent liquidator should outweigh considerations of allocating estates to Attorneys at law on equality grounds.

Should the bankruptcy petitioner, or where applicable other creditors, have a say in whom the court appoints as liquidator?

Rules on this point vary from country to country. In Denmark, for example, creditors are given a certain opportunity to influence which liquidator is appointed. The considerations relied upon in Iceland favour a liquidator safeguarding the interests of all creditors rather than prioritising the largest creditors at the expense of others. I consider that the Icelandic approach has worked well to date and that the remedies available to creditors to challenge a liquidator’s work are, for the most part, satisfactory.

Expertise of the liquidator

Your research indicates that liquidators' expertise is not systematically documented. Should the courts do better in this regard?

The considerations set out in the non-binding rules on the appointment of liquidators are, in my view, a significant improvement; however, the courts still lack a consistent system for maintaining these records. The Judicial Administration could, for example, create a shared database for all courts to keep information on liquidators, such as experience, number of estates allocated, expertise, and complaints received about the individual that have not been dismissed as unfounded.

Should stricter qualification requirements be introduced for Attorneys at law acting as liquidators in large estates where substantial financial interests are at stake, or where significant disputes exist among creditors?

In the thesis, I explore several ideas for changes regarding this issue. These include requiring that an Attorney at law must have assisted in a specified number of liquidations under a liquidator’s supervision before being eligible to receive estates in their own right. Another idea would be to set minimum requirements for expertise and experience in larger estates, for example, that the individual must have liquidated a certain number of estates before being allocated larger ones. A useful first step would be to incorporate more detailed conditions into the recommendations on appointing liquidators, setting them out with greater specificity.

The need for an improved framework and greater transparency

Currently, the courts maintain so-called "liquidator lists" of Attorneys at law willing to take on bankruptcy estates. Do you think the courts generally follow these lists?

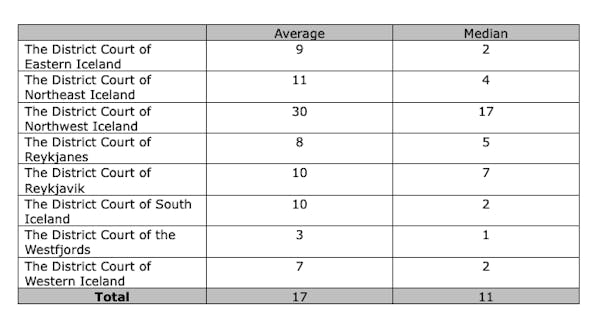

From the liquidator list published by the Minister of Justice earlier this year in response to a parliamentary question, it appears that there are considerable differences between Attorneys at law in the allocation of estates. The list does not tell the whole story, however, because some Attorneys at law have been appointed to larger estates that take a long time to liquidate and therefore receive fewer allocations. The District Courts of Reykjavík and Reykjanes have done well in ensuring equal treatment. Still, it appears that courts outside the capital area, in most instances, appoint Attorneys at law with offices within their judicial district. There are fewer Attorneys at law receiving estate allocations there. Consequently, the number of estates allocated to Attorneys at law outside the capital area is, in many cases, higher than in the capital area. The ten Attorneys at law who received the most allocations according to the liquidator list all share the characteristic that the majority of their allocations originate from courts outside the capital area, with their total allocations ranging from 73 to 124 estates. In the accompanying table, compiled from the liquidator list and covering the period 2012–2021, you can see the average and median number of estates allocated to Attorneys at law, broken down by each court.

Number of liquidators on the District Courts' lists

• the District Court of Reykjavík: 258

• the District Court of Reykjanes: 259

• the District Court of South Iceland: 284

• the District Court of Northeast Iceland: 49

• the District Court of Western Iceland: 146

• the District Court of the Westfjords: 20

• the District Court of Northwest Iceland: 20

• the District Court of East Iceland: 23

Do you believe that the decision to appoint a liquidator should be reasoned and where appropriate, appealable to a higher court?

I do not consider that to be necessary. In practice, providing such reasoning could cause considerable difficulties and would increase the courts’ workload. One of the principal reasons the appointment of a liquidator is not appealable to a higher court is precisely that the appointment is not reasoned, making it inappropriate for an appellate court to assess the correctness of the appointment. If a change were introduced requiring that liquidator appointments be reasoned and appealable, this could delay the liquidation and entail significant costs. However, I do consider that there is a need for a better framework and greater transparency regarding how bankruptcy estates are allocated. Regular publication of the liquidator list, broken down by the number of estates allocated, would be one step towards increased transparency.

Is there a lack of authority to reopen the liquidation proceedings?

Should the procedural framework be amended so that a liquidator cannot formally conclude the liquidation without the District Court’s consent or confirmation, thereby preventing the liquidator from evading potential reprimands by closing the liquidation?

I consider that such an approach would merely increase judges’ workloads and would, in most cases, be of limited value. To address the criticism that a liquidator can conclude the liquidation and thereby avoid the possibility of reprimands to their work, it would suffice to enact a statutory power for the District Court to reopen the liquidation if objections are raised that the court considers to be well-founded, or to provide a statutory power to pursue reprimand cases irrespective of the closure of the liquidation. However, I consider that reopening the liquidation for the purpose of conducting reprimand cases may pose difficulties; in my view, the better option is to allow reprimand cases to be pursued regardless of whether the liquidation has formally concluded.